A Trip to the Glass House

I visited the Glass House in New Caanan, Connecticut this weekend and I felt like logging some reactions.

I’m not a student of architecture but you don’t have to be to recognize this architectural icon. Designed by Philip Johnson and constructed in 1949, this is one of those ”shock of the new” artifacts that’s often cited as an architectural parallel to Picasso’s Guernica or Jackson Pollack’s Blue Poles. This unadorned thing with no opaque walls was offered to the world as a home, a place where future people would live in a modern world. Shocking indeed.

Glass House is set down a walking path below a main road in New Caanan, one of the wealthiest towns in the United States. Average people don’t live there. Rich people don’t live there. Wealthy people live there. And Johnson was quite wealthy. He bought no less than 49 acres of land on which to situate this structure. It sits on a promontory overlooking a bucolic wilderness. From no vantage point can any indication of civilization be seen. Sitting inside the house, Johnson could imagine that he was in his own manicured paradise, one that excluded all of humanity save for those special guests fortunate enough to be invited to his social events.

It’s a beautiful object from the outside; a glass box with a rectangular footprint held together by what seem to be impossibly thin ribbons of black metal. From the outside, you can see a brick silo and a few pieces of furniture. it’s pleasurable to look at. From a distance, I couldn’t wait to get inside, to experience what it was like to be inside.

Crossing the threshold, the first thing that struck me was its relative emptiness and how much echo there was. The intense echo effect from all of the hard, unyielding surfaces made it feel like being inside a shipping container (or what I imagine it’s like to be inside a shipping container). High echo is not something you associate with being in a home. It’s something you associate with being in a parking garage.

The house contains (in theory) everything a single person would need to survive a weekend: a kitchen counter, a small stove, an under-counter mini-fridge, a desk, a dining table, some living room furniture, a bank of closets/drawers, and a bed. A bathroom is tucked away in the fireplace silo. (It’s the one place you can retreat to for privacy.) Artificial lighting is scarce and small. Decorations include a free-standing painting and a couple of thin, wispy plants. There are no shades or drapes to block the late-day sun.

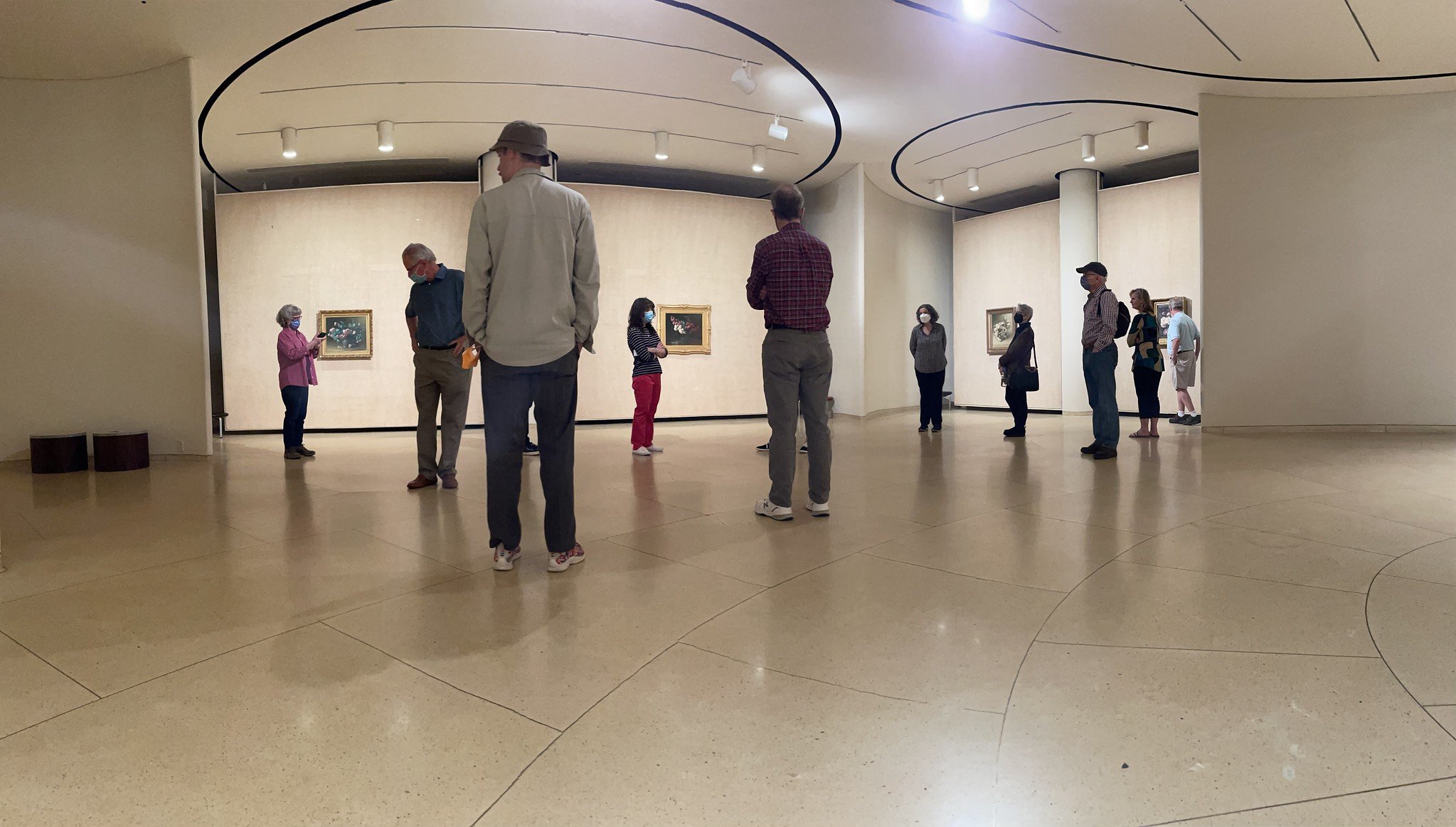

View from the “kitchen.” The gentleman in the middle of the photo regards the “living room,” delineated by the white carpet.

I experienced the disjoint between what it’s like to experience an object in a book and what it’s like to experience it in real life…in this case to stand inside of it in real life. Sometimes the real thing is better than what’s in your head. In this case, not so much. The house felt cold, sterile, and decidedly uninviting. It wasn’t a place I could imagine living in for more than a weekend. Even though it was in the exact state in which Johnson inhabited it, it felt like a carefully staged exhibit; if any element was out of place, the field of perfect symmetry would be destroyed.

The Glass House is less a “house” and more of an anti-house. It’s an intellectual conception of a home without actually being home-like…something warm, comfortable, inviting—a refuge from the public world where you can relax. It’s impossible to imagine ever feeling relaxed in this structure at night. Your every move could be watched by anyone who happens to walk onto the property in the dark. There’s nothing to stop anyone from doing so. Who could sleep soundly under those conditions?

Pleasant dreams! This is a sleeping environment that only a monk could love.

So, in the end, the Glass House seems like a brainy curiosity, an exercise in trying to do something completely new. It’s also an exercise in ego, designing something with the goal of becoming known. Johnson proved that a small structure could be made from Jet Age materials, but no home is made like this today. It didn’t usher in an era of glass and steel home fabrication. If anything, it’s a tiny version of the Seagram Building, a skyscraper designed by Johson and others to efficiently hold a thousand office drones. As a personal living space, the Glass House seems an impractical dead end.

The 49 acres of Johnson’s property hold other projects that he added in the succeeding decades, two of which I found more interesting than the Glass House itself. The first is the “Painting Gallery”, a hidden structure buried in the hillside that is entered through an easily-overlooked door that looks like an entrance to a bomb or tornado shelter. Inside is a stunning art gallery. There are three axes around which vertical panels are mounted and which can be rotated to show different works. The gallery was so large and stunning that I assumed he opened it for public shows. No, the docent said; this was his personal art collection for his own viewing and those he invited over for parties. Imagine.

Imagine building this just for yourself. The idea of rotating display walls was pretty nifty, though.

Lastly, we entered the Sculpture Gallery. This was a really fascinating space with a slotted glass ceiling, an Escher-like maze of stairs, and a mesmerizing pattern of slashing shadows thrown over everything by afternoon sun. This seemed to be the most compelling structure with a more traditional form including walls and distinct rooms. Even though it was built to house Johnsons’s personal sculpture collection, the docent said he considered relocating his living quarters to this space but eventually decided that the constant overhead sun exposure and the associated heat made it unacceptable. (Weird, considering it’s not really acceptable for artworks made of unstable materials either.)

The Sculpture Gallery. Not climate controlled. Would make a great a greenhouse.

So, that was the tour. Only after I got home and decided to google some of what I had seen did I learn that as a young man, Johnson had worked as a writer for Father Coughlin, subscribed to the idea that whites were being “out bred” by races with higher fecundity, and was sympathetic to the pre-WW II Nazi regime. All-in-all, kinda fashy. Of course, he disavowed all of this later in life, but he was no child when he aligned himself with these causes. Hard for this not to color my perception of the visit to his most famous work.